Virus Origins and Gain (Claim) of Function research

By Martin Neil and Jonathan Engler

Source: wherearethenumbers.substack.com

Nov 15, 2024

“I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.” – Richard P. Feynman

Summary

A thorough review of the available evidence suggests that the emergence of a novel engineered virus is the least likely explanation for the event known as the ‘covid pandemic’.

Notably:

- The discovery of ‘novel’ viruses is a function of how determined we are to find them – the more we look the more we find, suggesting that the attribution of novelty to a virus is as much the result of a politicised process rather than something based on an objective analysis of its properties.

- The features of SARS-CoV-2 do not appear to be as ‘special’ or ‘unique’ as claimed.

- There is no good evidence that the many and complex hurdles in front of deliberately engineering viruses to become more pathogenic or transmissible in humans have been overcome.

- The theory that there was a long-standing but hitherto undetected virus endemic in animal (and possibly human) reservoirs is difficult if not impossible to falsify.

- There are other explanations which could explain the sudden and rapid global appearance and spread of a specific sequence than the spread of a novel virus. The available virological and epidemiological evidence does not adequately support either the lab leak or the wet market theories for the origins of the virus.

We therefore suggest that it would be more apt to refer to ‘Claim-of-Function’ than ‘Gain-of-Function’ research.

Virological research with the intention of enhancing pathogenicity is, nevertheless, unethical and unnecessary and as such should cease; this is true even though we believe the evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that the ‘covid pandemic’ was an iatrogenic phenomenon and was not caused by a novel and deadly virus. In this regard if there actually was a function gained by the virus it was the power to help trick humanity into a dramatic act of self-harm.

In response to the core thesis presented here, many people respond with various formulations of ‘Fauci et al were covering it up, that surely proves a lab leak caused the pandemic’. That analysis is one which goes to motive, which, in determining whether a crime has been committed is of evidential value, but is in fact circumstantial, most jurisdictions requiring more direct evidence to deliver a guilty verdict. This article is not focused on motive, but is instead focused on the more important question ‘what evidence is there for the claim that Gain-of-Function research actually caused a global pandemic?’ (For a possible explanation as to how the ‘lab leak cover-up’ may be connected to the ‘pandemic response’ see here.)

There is nothing novel about a novel virus

Fields Virology is cited as one of the most authoritative references in virology, including virus biology as well as replication and medical aspects of specific virus families. Chapter 28 of Volume 1 of this book was written by Masters and Perlman and provides some fascinating insights into our knowledge of coronaviruses which are considered to infect humans, including:

- HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1 were only discovered recently, in the post-SARS era (2002), even though each is prevalent globally and has been in circulation for a long time.

- Four known coronaviruses—HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1—are endemic in human populations. The first two of these are thought to cause up to 30% of all upper respiratory tract infections.

- HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1 can be found worldwide, causing up to 10% of respiratory tract infections.

- Initial reports following its “discovery” suggested that HCoV-NL63 was associated with severe respiratory disease; however, subsequent population-based studies showed that most patients developed mild disease, similar to those infected with HCoV-229E or HCoV-OC43.

- Also, HECV-4408 coronavirus was first detected in Germany in 1988 and is associated with acute diarrhoea in humans and is (likely) related to bovine coronaviruses. However, the literature on this virus is incredibly sparse and there seems to be no active research interest in this virus at all.

Pyrc et al report that HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E were discovered in the mid-1960s and since have been found to be prevalent worldwide. Though it isn’t quite clear how prevalence was established, it does appear that the assumption was they were already endemic rather than novel, either created in a laboratory or by zoonosis. HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1 were coronaviruses that were unknown to science until relatively recently, despite causing a high proportion of respiratory infections worldwide and probably having done so for centuries, if not since the dawn of time (as described later). A full one quarter of coronavirus infections were attributable to these coronaviruses that were hitherto completely unknown to science. Also, as we explain later, upon discovery, one of these was associated with severe respiratory disease, yet subsequently careful population-level analysis proved this to be false.

There are striking similarities between the histories of HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1 coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2. They were all novel to detection, two were associated with severe disease and the severity of two of these was significantly downgraded once the population data was analysed.

Yet as regards the origin of SARS-CoV-2, we are presented with a choice between two competing stories: either it was the product of a lab-leak, or it leapt into existence by zoonotic transmission from animals to humans, and in both cases, this happened shortly before its first detection. The third possibility – pre-existing endemicity – is hardly discussed as a possibility. An analogue of this situation would be turning on the high-resolution Hubble telescope and declaring that the newly detected exoplanets (planets revolving around stars other than our sun) sprang into existence at, or just before, the moment the telescope was turned on rather than consider they had already been there for aeons past.

Why are some newly discovered coronaviruses (HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1) assumed to be already endemic, whereas others are assumed, upon discovery, to be entirely novel and capable of starting a pandemic? This should be an important scientific question, but it is one which few have bothered to ask, let alone attempt to answer.

An interesting article discussing the discovery of a new virus, Redondoviridae, from 2019 asks the question: how do you find a virus that is completely unknown? They point out that:

“Viruses, the most abundant biological entities on earth, are a scourge on humanity, causing both chronic infections and global pandemics that can kill millions. Yet, the true extent of viruses that infect humans remains completely unknown. Some newly discovered viruses are recognized because of the sudden appearance of a new disease, such as SARS in 2003, or even HIV/AIDS in the early 1980s. New techniques now enable scientists to identify viruses by directly studying RNA or DNA sequences in genetic material associated with humans, enabling detection of whole populations of viruses — termed the virome — including those that may not cause acutely recognizable disease. However, identifying novel types of viruses is difficult as their genetic sequences may have little in common with already known viral genomes that are available in reference databases.”

They then go on to report that researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have identified a previously unknown viral family, which turns out to be the second-most common DNA virus in human lung and mouth specimens, where it is associated with severe critical illness and gum disease!

So, are novel viruses really that novel? As we have seen, since the 1980s there have been at least six “novel” new coronaviruses detected (MERS-CoV, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1 and HECV-4408), an average of one every seven years. How can we rule out the possibility that, had they doubled their efforts to find these apparently novel viruses, they wouldn’t have found twice as many?

Using MERS-CoV and SARS to historically establish the fallacy of a single cause

In a 2014 paper MacIntyre recorded that the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was a newly emerged infection affecting humans in the Arabian Peninsula, Europe, and North Africa. Most MERS-CoV cases have been associated with hospital outbreaks in Jordan, KSA, UAE and France. These clusters have been somewhat variable in clinical features, with the first outbreak in Jordan notably featuring renal failure, which does not feature as much, or at all, in other clusters, and would be an unusual feature of an illness caused by a respiratory virus1.

A single infectious agent should not manifest in such varied ways. Under an old-fashioned disease model MERS-CoV would be categorised as separate illnesses, and it is only because of the new-fangled way of looking at sequences and the fact that a sequence is detected (or suspected as present), that it is assumed the cause of there must be a single cause – “the virus”. However, this assumption is an example of the ‘fallacy of the single cause’ and has no clinical validity; it is an artifice.

The source and persistence of the infection in humans remains unknown, despite having infected 681 people and killed 204 over a 2-year period. Cases were concentrated in the Middle East and it appears not to have spread much beyond that region. Of note the author says:

“When the observed data were fitted to different disease patterns, the features of MERS-CoV fit better with a sporadic pattern, with evidence for either deliberate release or an animal source. There are many discrepancies in the observed epidemiology of MERS-CoV, which better fit a sporadic than an epidemic pattern.”

Although the virus had been found in bats and in camels, it was speculated that most humans contracted the virus asymptomatically. Camels were believed to be the most likely source despite no particularly compelling evidence of transmission to humans from camels, except it had been found in some camels2. Larger outbreaks have occurred in South Korea in 2015 and in Saudi Arabia in 2018.

Furthermore, speculation about bioterrorism rears its ugly head (without any evidence):

“Finally, the discrepant epidemiology warrants critical analysis of all possible explanations, and involvement of all stakeholders in biosecurity, and deliberate release must be seriously considered and at least acknowledged as a possibility.”

Gardener and MacIntyre dispute that the pattern for MERS-CoV should even be considered sporadic never mind epidemic because even though it was in circulation during the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages to Saudi Arabia, supposedly perfect conditions for an epidemic, it did not visibly spread. They note:

“The risk factors associated with MERS-CoV include male gender, underlying disease, immunosuppression and hospitalization.”

They also say MERS-CoV was primarily a nosocomial infection (hospital acquired) associated with people already in hospital. They say that SARS was also predominantly a nosocomial infection.

In a comparison between SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV Khalid et al report that:

“The postintubation course was similar between the groups. Patients in both groups experienced a prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation, and majority received paralytics, dialysis, and vasopressor agents. The respiratory and ventilatory parameters after intubation …. and their progression over 3 weeks were similar. Rates of mortality in the ICU (53% vs. 64%) and hospital (59% vs. 64%) among COVID-19 and MERS patients were very high.”

Abid et al confirmed that MERS-CoV cases were complicated by bacterial and fungal infections. Half of patients had oxygen saturations less than 90%, and the majority who died did so after a prolonged period of ventilation. Antibiotics were given on admission to hospital (which may be too late, here).

SARS was first discovered in 2002 with the first known cases and was said to have caused the 2002-2004 outbreak, mainly in China (Andersen et al). Wikipedia provides a good overview of what is known about SARS, the most interesting difference to MERS-CoV being that the WHO declared that SARS disappeared as an acute respiratory syndrome in 2003 because of containment (attributed to public health measures). However, the virus failed to spread in 2003 and 2004 despite four laboratory accidents (here) and it is claimed to be persistent as a zoonotic threat.

Sound familiar?

The assumption is that there is infection, and it might spread worldwide, even though the patterns of spread defy currently authoritative epidemiological mechanisms.

- Infection is mainly acquired in hospital, yet the only assumption worthy of consideration is that a new virus has just recently emerged from nature or are speculated to be manmade – the possibility of pre-existing endemicity is ignored.

- The perceived high fatality rate, in already hospitalised cases, is assumed to be caused by the virus and is dissociated from the underlying medical conditions of the patients.

- The possibility of asymptomatic spread is simply assumed, yet no evidence for this is offered. This hypes the possibility of a pandemic despite the alternative and simple conclusion being that if it was spreading invisibly, it therefore could not be that deadly.

- For both MERS-CoV and SARS, symptoms of both are nonspecific, causing flu like symptoms. Nothing was diagnostic. Radiographic evidence was also said to be diagnostic of SARS but as we found in our article on spikeopathy no radiological signs could distinguish between this and any other respiratory viral illness.

- It is acknowledged they can both lead to bacterial pneumonia.

- Wikipedia says that 72% of people required mechanical ventilation for MERS-CoV and ventilation was used for treatment of SARS.

- Antibiotic treatment for both SARS and MERS-CoV was discouraged, as per WHO guidelines.

- Both were diagnosed by PCR, but diagnosis on mere suspicion was encouraged by the WHO and CDC (a mere cluster of unexplained pneumonia would be enough).

Again, we see the fallacy of the single cause at play and are presented with these highly speculative single explanations about the diseases supposedly caused by these past epidemics are being caused by viruses and viruses alone.

The key thing here is that the mortality and morbidity of SARS and MERS-CoV are very likely hugely overestimated, and this is due to the confounding effects of inappropriate medical treatments and diagnoses based on presumptions of high prevalence and travel history. Hence, the apparent virulence and pathogenicity of newly discovered viruses appears to be regularly hugely overestimated soon after their discovery, only to be either massively downgraded later (HCoV-NL63) or the fiction of their severity to remain unchallenged (SARS-CoV-2, SARS, MERS-CoV). This playbook gets repeated again and again, such as more recently with H5N1 (here).

Would we recognise a novel virus when we see it?

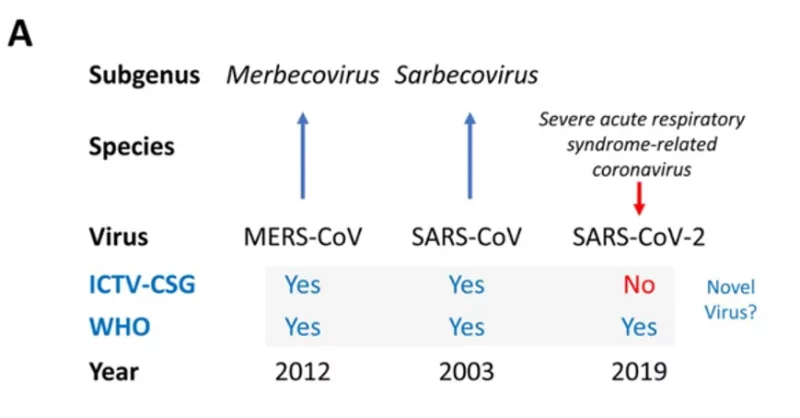

If we are told to accept SARS-CoV-2 as novel, such acceptance should be conditional on how robust the process was for appending the label ‘novel’ to the virus. In this regard it is useful to examine the decision-making process underpinning this decision (Engler).

In February 2020 the Coronavirus Study Group (CSG) International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV-CSG), which is responsible for developing the official classification of viruses and taxa naming (taxonomy) of the Coronaviridae family, assessed the novelty of the human pathogen tentatively named 2019-nCoV (pre-print on biorxiv Gorbalenya et al, Perlman and Drosten are co-authors).

The virus was temporarily named 2019 novel coronavirus, 2019-nCoV and renamed SARS-CoV-2 based on the CSG’s recommendations.

This is how they expressed the challenges in deciding novelty:

“The term “novel” may refer to the disease (or spectrum of clinical manifestations) that is caused in humans infected by this particular virus, which, however, is only emerging and requires further studies. The term “novel” in the name of 2019-nCoV may also refer to an incomplete match between the genomes of this and other (previously known) coronaviruses, if the latter was considered an appropriate criterion for defining “novelty”. However, virologists agree that neither the disease nor the host range can be used to reliably ascertain virus novelty (or identity), since few genome changes may attenuate a deadly virus or cause a host switch.

Likewise, we know that RNA viruses persist as a swarm of co-evolving closely related entities (variants of a defined sequence, haplotypes), known as quasi-species. Their genome sequence is a consensus snapshot of a constantly evolving cooperative population in vivo and may vary within a single infected person and over time in an outbreak.

If the strict match criterion of novelty was to be applied to RNA viruses, it would have qualified every virus with a sequenced genome as a novel virus, which makes this criterion poorly informative. To get around the potential problem, virologists instead may regard two viruses with non-identical but similar genome sequences as variants of the same virus; this immediately poses the question of how much difference is large enough to recognize the candidate virus as novel or distinct? This question is answered in best practice by evaluating the degree of relatedness of the candidate virus to previously known viruses of the same host or established monophyletic groups of viruses, often known as genotypes or clades, which may or may not include viruses of different hosts.”

So, novelty depends on a genome sequence which is a mere snapshot of a continually evolving dynamic swarm of co-evolving related entities, and thus the decision of what constitutes novelty is complex, owing more to judgement than objective analysis. It also depends on both the disease or clinical manifestations and the completeness or incompleteness of matches against other viruses. This presents a veritable smorgasbord of confounding and confusion of cause with effect, and in no way defines a ‘thing’ in and of itself.

If the strict match criterion of novelty was to be applied to RNA viruses, it would have qualified every virus with a sequenced genome as a novel virus. Therefore, they cannot be considered as isolated singletons with absolutely unique attributes, but rather as mutually overlapping families of individuals with shared attributes, making the idea of novelty, in an absolute sense, completely redundant. Thus, the ICTV apply a taxonomy to viruses that recognizes five hierarchically arranged ranks: order, family, subfamily, genus, and species (in ascending order of inter-virus similarity). Critics of this approach argue that genetic diversity can only be reliably expressed, mathematically, as pairwise distances between them and probabilities of overlap in genetic divergence, or to put it another way there can be no taxonomy in a swarm.

By the time the paper was published in Nature microbiology all reference to the difficulty and role of expert opinion in deciding the assignment of the name SARS-CoV-2 had been deleted, giving the impression that the decision was straightforward and not in any way controversial. If the name had remained 2019-nCoV it would probably have been considered just another cold virus and nothing to worry about.

In the pre-print the ICTV-CSG clearly label SARS-CoV-2 as not being a novel virus showing they came to a different decision to the WHO (and do so in red ink to make this clear):

There is some evidence of possible disagreement between the ICTV-CSG and the WHO (this paragraph didn’t make it into the paper published by Nature):

“In contrast to SARS, the name SARS-CoV-2 has NOT been derived from the name of the SARS disease and in no way, it should be used to predefine the name of the disease (or spectrum of diseases) caused by SARS-CoV-2 in humans, which will be decided upon by the WHO. The available yet limited epidemiological and clinical data for SARS-CoV-2 suggest that the disease spectrum, and transmission modes of this virus and SARS may differ. Also, the diagnostic methods used to confirm SARS-CoV-2 infections are not identical to those of SARS. This is reflected by the specific recommendations for public health practitioners, healthcare workers and laboratory diagnostic staff for SARS-CoV-2/2019-nCoV (e.g. WHO guidelines for 2019-nCoV). By uncoupling the naming conventions used for coronaviruses and the diseases they may cause in humans and animals, we wish to help the WHO with naming diseases in the most appropriate way (WHO guidelines for disease naming).”

They also hint at the possibility that both SARS and SARS-CoV-2 have suspect origins:

“Although SARS-CoV-2 is NOT a descendent of SARS and the introduction of each of these viruses into humans was likely facilitated by unknown external factors, the two viruses are genetically so close to each other that their evolutionary histories and characteristics are mutually informative.”

And then confess that differences in opinion about novelty are themselves not novel:

“Since the current sampling of viruses is small and highly biased toward viruses of significant medical and economic interest, the group composition varies tremendously among different viruses, making decisions on novelty group-specific and dependent on the choice of specific criteria selected by researchers. Practically, this means that definitive evidence for novelty in one group may not stand up to scrutiny in another.”

The idea that there are distinct species that fall into neat mutually exclusive categories is questionable. In the animal kingdom, what are presupposed as novel species or subspecies turn out to overlap. Take for instance the Liger – the hybrid offspring of Tigers and Lions. Similarly, different subspecies of bear interbreed quite easily. Life is on a continuum and if it isn’t possible to categorise animals and neatly place them in a taxonomy, might we be overconfident with viruses, organisms which are not readily observed, and about which we know much less? We would suggest that the ICTV are aware of these limits to the science of virology, especially since debates about virus taxonomy have raged since its inception, with many prominent scientists within the discipline arguing that descending hierarchical divisions are based on arbitrary and monothetic assumptions (see Murphy et al – introduction to the universal system of virus taxonomy).

Together the assignment of the word novel and the use of the name looks like the result of contentious political process or social construct, presented as a scientific one where all uncertainty, doubt and dispute have been stripped out.

Are spike proteins, inserts and furin cleavage sites dangerous or novel?

Much has been made of the fact that SARS-CoV-2 contains both a spike protein (the S protein) and furin cleavage site (FCS). This has caused much concern and controversy. Some claim that the spike protein is particularly dangerous and that the ‘unique’ furin cleavage site in this spike protein makes it responsible for high infectivity and transmissibility.

But are they dangerous and novel in and of themselves?

In Nature Xia et al say:

“The rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 …..a novel lineage B betacoronavirus.., has caused a global pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). It has been speculated that RRAR, a unique furin-like cleavage site (FCS) in the spike protein (S), which is absent in other lineage B [betacoronavirus], such as SARS-CoV, is responsible for its high infectivity and transmissibility. …

Therefore, it has been speculated that this unique FCS may provide a gain-of-function, making SARS-CoV-2 easily enter into the host cell for infection, thus efficiently spreading throughout the human population, compared to other lineage B betacoronaviruses.”

Its protrusion is described as odd and is described as ‘came through experimentation’. Speculative claims have been made that the FCS causes fibrosis. The supposed fragility of the spike protein against antibodies raises questions about the origin.

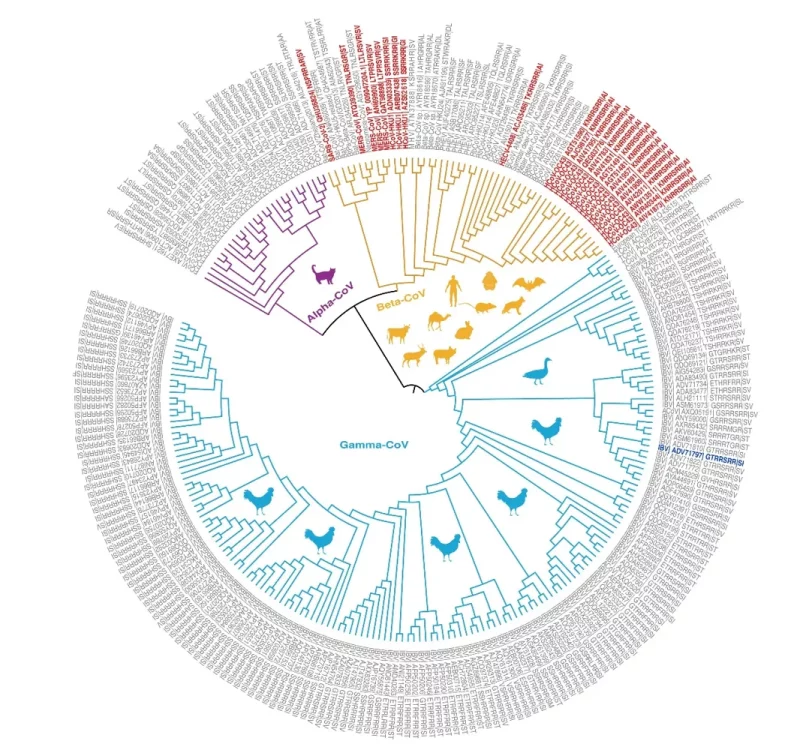

This review by Liu et al identifies:

“….248 other CoVs with 86 diversified furin cleavage sites that have been detected in 24 animal hosts in 28 countries since 1954.

….Besides MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, two of five other CoVs known to infect humans (HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1) also have furin cleavage sites. In addition, human enteric coronavirus (HECV-4408) has a furin cleavage site….”

The figure below shows the phylogenetic relationships of coronavirus spike proteins with furin cleavage sites.

Phylogenetic relationships of coronavirus spike proteins with furin cleavage sites.

The paper by Ambati et al makes the case that the composition of the SARS-CoV-2 FCS is very unusual, but ‘unusual’ means little without a comparison against the typical. They say:

“…presence of the 19-nucleotide long RNA sequence including the FCS with 100% identity to the reverse complement of the MSH3 mRNA is highly unusual and requires further investigations.”

They queried a database of 24,712 genomic sequences and calculated a coincidence probability of 3.21 × 10−11 for the SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage sequence, concluding that the FCS was man made.

Dubuy and Lachuer disputed this assertion by assessing the probability of coincidence that other viruses might exhibit these same features. Based on a careful probabilistic analysis, that considered that sequences are not independent, sequences are of different lengths and other factors, they found a coincidence probability of 0.0037 – orders of magnitude higher than that calculated by Ambati et al. This number itself might look small but if we express the odds of it being natural versus man-made, as a ratio, it is approximately one (a certainty).

Notice here that the key assumption in the work of Dubuy and Lachuer is that viruses might share the same features, perhaps because of parallel evolution but also because of co-evolution, whereby recombination takes place across species of virus, which is exactly what you might expect to take place in a viral swarm, as acknowledged by the ICTV.

Therefore, the FCS could have been created naturally and was perhaps simply a newly discovered virus that was already prevalent within the environment. Hence there may be nothing much that is truly novel about either the spike protein or the FCS. Masters and Perlman point out that:

- In many beta and gamma coronaviruses (e.g., mouse hepatitis virus, bovine coronavirus, and infectious bronchitis virus), the S protein is partially or completely cleaved by a furin-like host cell protease into two polypeptides…. which are roughly equal in size.

- Currently available structural and biochemical evidence accords well with an early proposal that S (spike) is functionally analogous to the influenza HA protein.

Likewise, much is made of the fact that the spike binds to human ACE2 receptors. Again, turning to Masters and Perlman:

“The receptor for SARS —angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)—was discovered with notable rapidity following the isolation of the virus.

……

ACE2 also serves as the receptor for the alphacoronavirus HCoV-NL63 and the corresponding structural complex for that virus reveals that the HCoV-NL63 RBD (receptor-binding domain) and the SARS RBD bind to the same motifs.”

So here we have another coronavirus, which was previously pronounced as being ‘deadly’ that also uses the ACE2 receptor, but which caused (in the main) mild respiratory disease.

It should be noted that ACE2 is expressed in less than 1% of human lung cells (here), being most abundant in the alveolar type II cells, which themselves are only 5% of the alveolar surface area, the other 95% of the area being covered by squamous alveolar cells. Hence it is debatable whether human lung function is critically dependent on ACE2 (as it might be in mice specially bred to have human ACE2 receptors).

Much controversy has been attached to the pre-publication, and subsequent withdrawal of a paper by Pradham et al claiming to have found a glycoprotein, called gp120, in the spike of the 2019-nCoV virus. This protein is thought to be specific to the HIV virus alone and given this, it suggests that the virus must be man-made. The 2008 Nobel prize winner Luc Antoine Montagnier replicated the finding and independent researchers have confirmed the finding since (Rose). Also, coincidentally or otherwise, another laboratory in Wuhan, funded by Germany, was working on an HIV vaccine, which may have been the source of the outbreak (Kogon).

Is gp120 unique to the HIV virus? Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) has been identified as the progenitor to HIV, and in SIV it is present on the SIV spike protein. Given recombination events between HIV or SIV and coronaviruses are not beyond the world of possibility, that SIV is the source for the presence of gp120 in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein cannot be discounted. We actually have no idea how much HIV and SIV are ‘out there’, and this notion has received zero attention, but surely the absence of evidence cannot therefore be assumed to be evidence of absence3 (note that asymptomatic HIV infection can last more than 10 years and the latency of SIV infection is largely unstudied).

We can conclude that:

- Spikes on coronaviruses are nothing special.

- Spike proteins are similar or common to proteins in other viruses, including influenza.

- FCSs are common. But the vast majority of the 248 identified (so far) have not been studied anywhere near as closely as SARS-CoV-2.

- ACE-2 receptors are used by one other coronavirus, HCoV-NL63, that is not considered deadly.

- Arguments that ‘unusual inserts’ must be man-made might be contradicted by parallel evolution or co-evolution between viruses ‘in the swarm’.

Hence, we see no reason to believe that the spike protein or FCS should be a source of special and unique concern in SARS-CoV-2. Even those ‘unusual inserts’ that supposedly make the virus remarkable may indeed be unremarkable, given it appears much more likely (if not a certainty) that other viruses might contain the same features by natural co-evolution between viruses.

Novelty of the SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site

Much of the argument about the origin hypothesis for SARS-CoV-2 revolves around the novelty of specific features of the virus and whether these resemble viruses known to be extant in nature or which are man-made (and are coincident with submitted research proposals).

An overview of the evidence supporting the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 was man-made in a laboratory can be found here. An entertaining and robust article discussing the observational evidence supporting either of these has been written by PANDA.

The lab theory is partly based on the evidence that no bat colonies have been found to be infected by the exact virus, hence the virus had never previously existed in the natural world. The implication it was man-made was then supported by the revelation, obtained by FOIA4, of the existence of the DEFUSE project proposal, an application to DARPA (a Pentagon research agency) for a grant to enhance SARS-like bat viruses (we will see later that this was not a unique ambition).

The idea of a lab leak is presented as shocking, but Nass has documented 309 lab acquired infections and 16 escapes between the years 2000 and 2021, including some which caused several deaths. Yet caused no pandemics.

The pre-print paper from Bruttel et al argued that SARS-CoV-2 is man-made because of the ‘endonuclease fingerprint’ (endonuclease recognition sites BsmBI/BsaI) found in SARS-CoV-2. BsmBI/BsaI are commonly used for molecular cloning. They say:

“We found that SARS-CoV (original SARS) has the restriction site fingerprint that is typical for synthetic viruses. The synthetic fingerprint of SARS-CoV-2 is anomalous in wild coronaviruses, and common in lab-assembled viruses…

….The restriction map of SARS-CoV-2 is consistent with many previously reported synthetic coronavirus genomes, meets all the criteria required for an efficient reverse genetic system, differs from closest relatives by a significantly higher rate of synonymous mutations in these synthetic-looking recognitions sites, and has a synthetic fingerprint unlikely to have evolved from its close relatives. We report a high likelihood that SARS-CoV-2 may have originated as an infectious clone assembled in vitro.”

The proposal presented here is that DEFUSE, and the Wuhan lab engaged in Gain-of-Function research, where the genome of a known virus is amended to create some additional desired functionality such as enhanced transmissibility, pathogenicity (enhanced is the important word here – creating equivalent pathogenicity or transmissibility to an existing virus isn’t the goal, the goal is to ‘gain’ this new functionality).

The fundamental assumption underlying GoF research is that any phenotype (trait or function) can be identified and directly matched to a one or more specific genotypes that together create that effect in the target species, and that by amending or replacing these genotypes in a special way, a desired functional phenotype can be created. A virus created by GoF could then be used as bioweapon or to be one step ahead by creating anticipatory treatments for potential future bioweapons or pandemic viruses.

Is engineering of more lethal viruses possible? The curse of dimensionality

A counter argument to this has been presented by Wu who analysed 1316 betacoronavirus and 1378 alphacoronavirus genomes collected before 2020 and found that a significant subset of these had the same unusual endonuclease fingerprint characteristics (BsmBI/BsaI) associated with SARS-CoV-2. Hence it might not be that unusual after all, and of Bruttel et al he said:

“….conclusions can be biased by an analysis of a limited number of coronavirus genomes and does not consider the dynamics of endonuclease recognition sites during viral evolution. Here, I provided a thorough investigation on the BsmBI/BsaI map in betacoronavirus, alphacoronavirus, and SARS-CoV-2 genomes.”

“… the pattern of BsamBI/BsaI restriction enzyme recognition sites in alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus is very diverse, and SARS-CoV-2 is not the only outlier in terms of the number and position of the two endonuclease sites.”

Hence it looks like these fingerprints are not unique to SARS-CoV-2 and are not necessarily associated with man-made interference.

Additionally, in a very interesting analysis Wu examined the feasibility of man-made development of SARS-CoV-2, focusing on Gain-of-Function insertions (reverse genetics) and serial passage (the process of growing bacteria or a virus in iterations):

“The challenge of engineering a new virus is not about the approach or tool for genome assembly but is generating a sizable mutant library and developing an efficient high-throughput screening system to identify the most infectious clones.

Wu estimated the costs of creating a Gain-of-Function virus by comparing the endeavour to the number of steps in the natural evolution of SARS-CoV-2 alpha to the omicron variant and extrapolating this to the evolution from the bat virus RaTG135 to SARS-CoV-2 (using the number of people infected by each variant worldwide and the timescales involved)6. Wu observed that:

“…it is reasonable to believe that it needs at least (80-250 million) experimental iterations to generate a new virus like SARS-CoV-2 from RaTG13….the laboratory consumable cost for a ∼250 million screening and testing experiment would easily exceed 10 billion dollars…. the cost of creating a SARS-CoV-2 would require the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s institute’s full investment for at least 100 years.”

On the implications of conducting serial passage:

“One infection cycle in cell culture is typically 1–3 days depending on the inoculated viral MOI (multiplicity of infection). So, to generate directed mutations on those 1182 nucleotides in RaTG13, we would need at least 121,230 days (332 years) by serial cell passaging. The challenge for animal-based serial passaging should be higher than the cell culture-based approach because of the longer viral incubation time and workload related to animal care. Thus, it is unlikely to obtain SARS-CoV-2 from serial passaging.”

By Wu’s reasoning it would be impossible for anyone to engineer a new viable virus that met a pre-prepared set of GoF requirements7. Not only would the DEFUSE project have had to have been very lucky to discover a virus that could be reliably cultured and had all required properties, but they would also have had to test whether it was viable for human transmission and increased pathogenicity.

A fascinating article, in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, explored Gain-of-Function research and reported that:

“Across biology, gene background is important. The same mutation can yield different results in different strains. This indicates that the impact of some of these mutations cannot be easily extrapolated. In turn, this suggests the pool of mutations that could make a virus a pandemic threat could be large, a problem for both gain-of-function research and alternative approaches. There are a host of other highly detailed virological arguments about why pandemic prediction is virtually impossible.

The gain-of-function thesis has been characterized by a belief that virology is akin to engineering; just define the (obviously small) numbers of permutations of mutations allowing a virus to cross over and transmit between humans, and “we’ll figure it out.” Biology and evolution were forgotten.

Ron Fouchier, a virologist in the Netherlands and one of the gain-of-function influenza protagonists, said in a 2014 conference that it might take him 30 years to work out the genetics of avian influenza transmission to humans. As most of us cannot see beyond two, 30 years was a euphemism for “don’t know.” Gain-of-function research can never deliver on its promise, which is the prediction of the next pandemic flu strain to allow the preparation of preventive drugs and vaccines.”

As we discuss later, we find that experiments undertaken to investigate ‘wild’ SARS-CoV-2 have amended the FCS and created new viruses. These experiments can and have been conducted, but that doesn’t mean the experiments are necessarily successful since no one knows whether the viruses produced are themselves going to be viable and can be made such that they meet the ‘transmissible and deadly’ (or any other) functional requirement. Ultimately, if the requirements are for a virus pathogenic to humans8, challenge studies will be required, not on mice but on humans. As far as we know they have not been performed, and in any case all the challenge studies done on wild SARS-CoV-2 have failed (here), and rather ignominiously so. Thus, any claims about functional viability might be partially validated in vitro, or in animal models, but cannot be fully validated in humans or in society at large. All we know is that viruses can be produced but you cannot guarantee that these will ‘go viral’ or be ‘deadly’9. Wu’s analysis suggests the whole endeavour is doomed to ruinous failure, if not simply impossible.

Is there actually any evidence that a viable virus has ever been engineered to match some pre-prepared functional specification and which could cause a pandemic? To our knowledge there are no end-to-end unambiguous successes. For instance, Masters and Perlman cite a case of Feline enteric coronavirus (FeCoV) where reverse genetics was used to swap S proteins from (presumably) virulent and avirulent strains, but the effect of this on pathogenesis is acknowledged to be unknown since experiments were done in vitro only.

An earlier controversy in 2014 surrounded GoF research centred on three forced-evolution experiments conducted on ferrets infected with H5N1 & H7N1 ‘bird flu’ viruses (documented here, here and here). The first two GoF experiments on ferrets demonstrated that transmissibility might be enhanced (but may not be predictive for humans), however the GoF variants produced were found to be insufficiently replication competent.

In the third of the studies cited above (by Sutton et al), researchers directly infected four ferrets, conducted serial passage experiments on these and then tried to infect naïve ferrets. They reported that a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus of the H7N1 subtype, with no history of mammalian adaptation, become capable of airborne transmission in the ferret model of influenza virus. This looks alarming and much might be made of the fact that all four of the directly infected ferrets were euthanised because they showed signs of severe disease. However, these ferrets were subject to serial passage numerous times rather than a single time as is the convention. Therefore, an alternative explanation for these animals being euthanised was not necessarily increased pathogenicity but probably that their immune system was simply overwhelmed by repeated reinfections. The authors reported a successful adaptation of bird flu to become capable of airborne transmission in ferrets but concluded that the GoF enhanced virus created may not have acquired the transmission efficiency required to cause a pandemic. Given the small sample sizes involved the question of increased pathogenicity in ferrets infected by the GoF variant was inconclusive10, but the balance of evidence suggests that the GoF virus was less pathogenetic, in the lungs and bronchi etc., than the wild-type virus (as one might expect).

Given that Loss-of-Function (LoF) experiments, involving the removal of features of a virus, are commonplace, and are akin to developing attenuated virus vaccines, another nail in the coffin is this paper from Fauci himself, which admits that vaccine development is fraught with difficulty for respiratory viruses simply because of inherent rapid viral replication, error rate during mutation and antigenic drift. He says this (after the launch and injection of the covid-19 vaccines into billions of people!):

“Durably protective vaccines against non-systemic mucosal respiratory viruses with high mortality rates have thus far eluded vaccine development efforts.”

If these features make vaccine development for respiratory viruses difficult if not impossible then they also make virus development via Gain-of-Function equally, if not more, challenging (well, maybe actually just as impossible).

In mathematics this is called the curse of dimensionality. In many problems where each variable (protein, genomes, cells, virions) can take on several values, taking the variables together, a huge number of combinations of values must be considered, leading to a combinatorial explosion. This results in an exponential set of possibilities each of which must be considered and evaluated. In the biological domain things are even more challenging because of non-monotonicity – any phenotype (trait or function) cannot be directly matched to a single specific genotype; hence the problem is not reducible and there exists no algorithm that can feasibly search the space of possibilities and identify the single genotype sequence that delivers the phenotype required. RNA viruses are mutation machines with the potential to adapt to a new host hence, even if a stable virus function is isolated, it will quickly mutate and lose this newly gained functionality (Wain-Hobson).

Therefore, to create a genuinely pandemic-causing coronavirus would probably involve the re-engineering of one or more coronaviruses and would simply not be possible using GoF research. Only the timescale of natural evolution could deliver the time and space needed to create both viable and non-viable combinations in a way that man cannot. Evolution (or God) is needed to defeat the curse of dimensionality.

Gain (or loss) of function experiments

Research on SARS-CoV-2 naturally involves using the tools of the trade, including applying reverse genetics to engineer variations in the virus. Such variations might include amendments to the furin cleavage site and the spike protein11.

In January 2021 Johnson et al carried out a LoF experiment using reverse genetics, observing that four hamsters infected with wild virus lost weight and showed some signs of infection compared to the LoF arm. They also found that the LoF virus was replicated more efficiently, defying expectations. When they repeated the experiment with transgenic mice, they found no differences in viral burden but based on the totality of evidence they concluded the LoF mutant produced reduced disease and replication at early times after infection, as compared to wild-type virus. They also used transgenic mice with hACE2 receptors (12 per arm) to examine pathogenicity, claiming there was evidence that the wild virus caused more weight loss, but with no differences in viral burden in the lungs or brain. To determine the functional effects on the lung, mice were mechanically ventilated to measure biophysical parameters, with the wild type mice showing more damage. Histopathology confirmed this.

In July 2021 Davidson et al cloned WT (wild type) SARS-CoV-2 and produced variants with GoF enhancements by engineering spike variants. Laboratory results showed LoF, specifically the deletion of the furin cleavage site, did cause higher infection rates of human endothelial cells (airways), and when they tested viral transmission on eight ferrets, they found 2 of the 4 ferrets, cohoused with ferrets intentionally pre-infected with WT, showed signs of infection. And 0 of the 4 ferrets, cohoused with ferrets intentionally pre-infected with the GoF variant, showed signs of infection. They say:

“We show that, in contrast with WT SARS-CoV-2, a virus with a deleted furin CS did not replicate to high titres in the upper respiratory tract of ferrets and did not transmit to cohoused sentinel animals, in agreement with similar experiments using hamsters”.

This study uses such a small sample size that the results are not significant, and we don’t know whether infection had any effect on pathogenicity. No ferrets from either experiment showed appreciable fever or weight loss. When they used a ‘competitive’ 70% WT and 30% LoF mutant mix the results were not clear at all. In some ferrets the lost function mutant dominated in those inoculated with the mixture, and of the four co-housed ferrets only one was infected by transmission. This makes the results difficult to interpret.

In a similar study, in February 2021, Zhu et al, used naïve hamsters co-housed with a single infected hamster, examining changes to the furin cleavage site using six hamsters in each arm (wild type and LoF arm). Despite heroic applications of statistical skill on such a small sample size the results are, not surprisingly, poor and unconvincing. The hamsters infected with the wild type virus did show around a 10% weight loss, whilst the hamsters infected with the LoF variant put on weight; there seems no reason why weight should increase, suggesting experimental confounding. The other results were no more persuasive, unsurprising given the small sample sizes.

In 2024 Valleriani et al conducted a much larger study using 150 transgenic mice expressing the hACE212 receptor, on the assumption these are permissive of SARS-CoV-2 infection and believed capable of developing severe disease (hence they are vulnerable to spike). Again, the comparison was carried out using a LoF arm. They say the LoF infected mice exhibited reduced shedding, lower virulence at the lung level, and milder pulmonary lesions. The mice in the LoF arm had a slightly higher survival rate and lower clinical scores than the wild type of virus.

If we take these experimental results at face value, they suggest that the LoF variant had higher transmissibility but lower pathogenicity, and the GoF variant had lower transmissibility and higher pathogenicity13, thus illustrating the inherent trade-off in these functional characteristics: you cannot have both a highly transmissible virus and one that is highly deadly. This might confirm the challenges in overcoming the curse of dimensionality – it being near impossible to make changes that can deliver both functions.

Note that in all these experiments there were no controls using other coronaviruses or influenzas viruses for comparison with SARS-CoV-2. We just don’t know how these LoF or wild virus results compare with common colds or influenzas. We also do not know what might happen if we removed FCS, or other genes, from these other coronaviruses. Would they become more pathogenic or transmissible? Are they already more pathogenic or less? Also, there were no tests to rule out bacterial pneumonia or other competing pathogens, which may have confounded the experiments.

There has been some discussion of pathogenesis associated with spike in many other coronaviruses, such as that by Millet and Whitaker published in 2014; however the correlation between pathogenesis and the spikes of particular coronaviruses are biased, simply because they are based on heavily confounded observation data (E.g. the spike for MERS-CoV is assumed to be more dangerous because it is associated with a ‘pandemic’, whilst those from coronaviruses that don’t have that associated are not). This is an important point – if the mortality data from previous pandemics is biassed by treatment protocols and medical negligence, how do we know the spike, or some other feature, is genuinely the driver of mortality?

The vast differences in symptoms for SARS-CoV-2 reported in different countries, for patients supposedly infected with the same virus, should raise alarm bells, since it suggests that reported symptoms were being confounded by location and test results (Neil et al). It is an inversion of reality to claim that the same virus causes different symptoms, occurring in different geographical locations, when historically different viruses (especially those associated with respiratory illnesses) have caused the same symptoms world-wide.

Published GoF and LoF experiments are unpersuasive on the point of our ability to engineer viruses to meet functional requirements. The absence of comparative controls is enough to confirm this, as are issues related to heterogeneity of symptoms from a supposedly engineered virus. It therefore remains an open question as to whether all coronavirus infections appear to be relatively non-pathogenic to humans, with or without the spike or FCS or any other inserts, man-made or natural, and that SARS-CoV-2 might be no different in this regard.

Contradictory evidence on zoonotic origins

Let’s turn to animal reservoirs to examine estimates of the phylogenetic origins of the virus. Munnik et al report that SARS-CoV-2 can infect domestic lions, tigers, cats, dogs, ferrets, hamsters, tree shrews, rabbits and even tigers in zoos. But not pigs or poultry (so far!)

They studied a zoonotic outbreak of infection of Dutch mink farms in 2020.

“A high diversity was observed in the sequences from some mink farms, which is likely explained by multiple generations of viral infections in animals before the increase in mortality was detected. ….

….the investigation has failed to identify common factors that might explain farm-to-farm spread.”

This could mean that the virus was already circulating in mink farms for some time before it was identified.”

Might it be possible the virus was already in the mink?

In 2020 Boni et al investigated the evolutionary origins of SARS-CoV-2, and reported:

“SARS-CoV-2 itself is not a recombinant of any sarbecoviruses detected to date, and its receptor-binding motif, important for specificity to human ACE2 receptors, appears to be an ancestral trait shared with bat viruses and not one acquired recently via recombination….

Divergence dates between SARS-CoV-2 and the bat sarbecovirus reservoir were estimated as 1948 (95% highest posterior density (HPD): 1879-1999), 1969 (95% HPD: 1930-2000) and 1982 (95% HPD: 1948-2009), indicating that the lineage giving rise to SARS-CoV-2 has been circulating unnoticed in bats for decades.”

If it has been circulating unnoticed in bats for decades, why wouldn’t it have been circulating in humans for decades also? And by decades we mean any point between 1879 and now?

This fascinating result has been much ignored. In 2024 Holmes in his widely cited work on the emergence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 barely mentions the paper and doesn’t cite the conclusions.

Markov et al also studied the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 examining:

“ …the selective forces that likely drove the evolution of higher transmissibility and, in some cases, higher severity during the first year of the pandemic and the role of antigenic evolution during the second and third years.”

They found:

“After the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in humans, for the first nearly 8 months the virus seemed to exhibit limited apparent evolution. This was partially due to the relatively small global virus population, while spread was still not ubiquitous, and later as a result of non-pharmaceutical interventions in many parts of the world, and partially an artefact of virus undersampling.”

It took 8 months for the first divergent SARS-CoV-2 lineages to appear…., marking a turning point in the pandemic from an evolutionary point of view. The first three such lineages, later termed VOCs Alpha, Beta and Gamma, emerged independently in different parts of the world and were the result of puzzling higher evolutionary rates. The sheer number of mutations involved in VOCs is particularly striking from an evolutionary point of view.”

This suggests that at the start of the pandemic the virus was a standardised copy identical in every way, but by the end of 2020 there were many. However, on the mink farms in the Netherlands we find minks with a very high range of diversity in sampled sequences suggesting it was present in the animal reservoir well before 2020. How can the human population be infected by a standardised version of SARS-CoV-2 yet animals are found with variants, and still no bats are found with SARS-CoV-2 at all. And careful phylogenetic analysis suggests progenitors of the virus has been circulating unnoticed in bats for decades (maybe since 1879?).

Despres et al looked at the wildlife in Vermont to see if they could detect SARS-CoV-2 and found none in the wildlife throughout the state, including deer, despite most published North American studies finding SARS-CoV-2 within their deer populations. They cited “environmental and anthropogenic factors” as the reason for this14.

Kumar et al conducted global sequencing of SARS-CoV-2, combined with computational methods, to identify the most recent common ancestor of the virus, suggesting that the Wuhan patient zero was not the index case, nor gave rise to all human infections. The inference then is that the progenitor of the virus was spreading worldwide months before the outbreak in Wuhan. They claimed to have identified the progenitor (root) genome of SARS-CoV-2 by measuring ‘coronavirus diversity’.

A critical limitation of phylogenetic analysis is the assumption there is no recombination between species and sub-species of virus. Instead, it is assumed that variation occurs ‘within’ and not ‘between’ species, and that genetic sequences that occur in one or more viruses might share a common ancestor in another. Given this there is no validity to the concept of a ‘root’ to the tree. Likewise, these issues cast serious doubt on any assumption that there is a predictable molecular clock that can be inferred from similar coronaviruses, and which itself remains constant over time. The ICTV as much as admit to this.

Given this, it is perhaps optimistic to believe that the discovery of the existence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater and other samples from 2019 (nicely summarised here), could in any way be definitive. This is because antibodies cover epitopes shared between different viruses, allowing our immune system to mount a highly diverse attack to destroy different viruses and variants without exhausting itself (how else might it defeat the combinatorial complexity of a continually evolving viral swarm?) It is therefore possible, if not certain, that the supposedly specific antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 could have been developed to counter a progenitor to SARS-CoV-2, containing the same epitopes, or to other similar coronaviruses, rather than to SARS-CoV-2 itself15.

There are too many contradictions here. Neither phylogenetic analysis or antibody studies can be fully trusted to provide the definitive origin and we have a much-ignored estimate of the evolutionary origins of SARS-CoV-2 going back to 1879. The possibility it may already have been endemic in the animal population for some time, as a result co-evolution of viruses in a swarm, therefore cannot be readily dismissed.

The hypothesis of zoonotic endemicity has therefore not been falsified (and to be fair it probably cannot be because the fundamentals are so poorly understood).

GoF research is routine and involves creating (infectious?) clones

Interestingly, the 2014 Millet and Whitaker paper (funded by the US NIH) ruminates on the potential for research on the FCS and is clearly advocating for GoF research focused there, thereby illustrating that it is a shared research theme in coronavirus research circles. They explicitly say:

“Overall, it seems likely that modulation of either of two protease cleavage sites by coronaviruses can have a profound impact on disease outcome, depending on the individual coronavirus.”

The FCS is an example of a protease cleavage site. This suggests that research on GoF/LoF focused on the FCS isn’t particularly unique to the DEFUSE project, thus devaluing significantly the hypothesis that because the DEFUSE project was researching into this precise area, the properties of the ‘novel’ virus must mean that it was man-made.

Bruttel et al says this about the routine use of reverse genetics to produce mutations (i.e. changing function):

“Making a reverse genetic system from a wild type CoV requires breaking the 30 kb coronaviral genome into 5-8 fragments, each typically shorter than 8kb (Almazán et al. 2006; Becker et al. 2008; Scobey et al. 2013; Zeng et al. 2016; Cockrell et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2017). To design a reverse genetic system, researchers often modify their synthetic DNA constructs from the wildtype viral genomes by introducing synonymous mutations that alter restriction enzyme recognition sites without significantly impacting the fitness of the resulting infectious clones.”

The first paper Almazán et al describes the engineering of a full-length cDNA (complementary DNA) clone from SARS. A cDNA clone contains the entire viral genetic information necessary for replication, transcription, and translation. To put it another way they have the potential to be infectious, just like the original virus they cloned. They use it:

“…..for the recovery of infectious virus and has been used for the generation of a large collection of deletion mutants of SARS-CoV”

A deletion mutant is a genetic anomaly in which a segment of a chromosome or DNA sequence is omitted during DNA replication, leading to the absence of specific nucleotides or entire chromosomal segments. This can result in altered gene function or expression. This is GoF.

Let’s look at Becker et al (Ralph Baric is a coauthor on this 2008 paper):

“Defining prospective pathways by which zoonoses evolve and emerge as human pathogens is critical for anticipating and controlling both natural and deliberate pandemics. However, predicting tenable pathways of animal-to-human movement has been hindered by challenges in identifying reservoir species, cultivating zoonotic organisms in culture, and isolating full-length genomes for cloning and genetic studies. The ability to design and recover pathogens reconstituted from synthesized cDNAs has the potential to overcome these obstacles by allowing studies of replication and pathogenesis without identification of reservoir species or cultivation of primary isolates. Here, we report the design, synthesis, and recovery of the largest synthetic replicating life form, a 29.7-kb bat severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-like coronavirus (Bat-SCoV), a likely progenitor to the SARS-CoV epidemic. To test a possible route of emergence from the noncultivable Bat-SCoV to human SARS-CoV, we designed a consensus Bat-SCoV genome and replaced the Bat-SCoV Spike receptor-binding domain (RBD) with the SARS-CoV RBD (Bat-SRBD). Bat-SRBD was infectious in cell culture and in mice and was efficiently neutralized by antibodies specific for both bat and human CoV Spike proteins. Rational design, synthesis, and recovery of hypothetical recombinant viruses can be used to investigate mechanisms of transspecies movement of zoonoses and has great potential to aid in rapid public health responses to known or predicted emerging microbial threats.”

This is clearly GoF research and was published 12 years before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Here is the title of the paper from Cockrell et al (2018):

“A spike-modified Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infectious clone elicits mild respiratory disease in infected rhesus macaques”.

This is GoF research.

Likewise, note that the studies on LoF we have already discussed previously, in principle, are implicitly no different from GoF. Hence GoF research is ongoing.

Also, it should be obvious that cloning viruses is straightforward and even quite routine in virological research and development. For instance, the Bruttel paper says:

“The BsaI/BsmBI map of SARS-CoV-2 is anomalous for a wild coronavirus and more likely to have originated from an infectious clone designed as an efficient reverse genetics system. The research goals and laboratory logistics of infectious clone technology can leave a previously unreported fingerprint in the genomes of infectious clones”.

Masters and Perlman discuss clones at some length and in noncontroversial terms.

A moratorium announced by the Obama administration was lifted in 2017 after three years (2014 – 2017), and despite the moratorium the US government continued to assess and fund some GoF experiments (here). So not a ban at all then.

It therefore appears to be the case that, like the DEFUSE proposal GoF research was and is still routine. Indeed, it looks like standard practice applied globally across many research groups studying coronaviruses.

If not lab leak or wet market, then how did “it” arise?

On the animal origins of SARS-CoV-2 Wu had this to say:

“Most recently, Wang et al discovered a high frequency of mammalian-associated viral co-infections and identified 12 viruses that are shared among different bat species by meta-transcriptomic analysis of 149 individual bat samples in Yunnan, China. The authors also found two coronaviruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 (92%–93% genetic identities), with only five amino acid differences in the receptor-binding domain of one genome compared to the Wuhan-Hu-1 strain. These findings indicate that viral co-infections and spillover are common in bats, which explains the high recombinant events in coronavirus and points to the origin of SARS-CoV-2 from recombinational exchanges among multiple related genomes.”

Now we should disclose that Wu graduated from the Wuhan Institute of Virology in 2012, and hence might be considered to have a conflict of interest, but his analysis does not appear to rely on new research and simply extrapolates from what is currently considered the current state of practice in virology. Moreover, he is currently at the University of Texas.

Of course, neither side of the argument can say how SARS-CoV-2 might have come to have been detected in humans, but it is not beyond possibility that it neither arose recently in nature, nor emerged from a laboratory but may instead have been with us for quite some time, lying low in the human population or in nature until it was discovered.

Let’s consider the explanation of the single point zoonotic event, in the Huanan seafood (wet) market in Wuhan sometime between October to December 2019 (molecular epidemiology described here). Does it seem unlikely that the virus arose spontaneously in the wet market at the same time GoF research was going on in Wuhan. What’s the chance of nature creating a new virus at that exact place and time? The probability would be astronomically low, especially given it supposedly might include bats, humans, and pangolins.

The patchy pin-point pattern of spread of SARS-CoV-2 offers strong support to alternative explanations for the origin of SARS-CoV-2, with mortality rising in spring 2020 only after lockdowns were implemented and not before, and morbidity only revealing itself as attributable to a new virus with the roll out of PCR testing. (Rancourt, Engler, Pospichal).

We can therefore speculate about alternative theories, two of which are pre-existing endemicity and virus clones, intentionally manufactured to create the impression of a pandemic. The first theory is one of pre-existing endemicity across the world (supported by existing T-cell immunity and other things). The second is that lab manufacture was involved, but not necessarily involving a leak from a laboratory in Wuhan, but ‘something’ was intentionally released first in Wuhan and then in multiple pinpoint locations worldwide. These theories need not be mutually exclusive but operationalizing these would require them to be coupled with a project involving high levels of mendacity and inventiveness.

Pre-existing endemicity:

- Imagine stealing a march on the science and discovering a coronavirus already endemic in humans but not in bats or camels (perhaps it spilled over zoonotically in the long distant past). You keep this secret because you realise this is an exploitable opportunity if you can successfully pull off a bait and switch. You apply for GoF research funding to engineer new viruses, for the benefit of humanity (vaccines etc.). You use the newly discovered virus in your research and maybe you might even toy around making some small changes. You feel confident enough to reveal these in the grant application because it might prove useful later. However, you know GoF is impossibly difficult (but you don’t admit this to your sponsors or the public) and you therefore cannot make it any more lethal or transmissible than it current is (which is not much anyway given it has been in the background maybe for aeons). Next, you create a vaccine for this virus (which also doesn’t work but that’s another story). All that would be left to do would be to create a test for this virus so that it can now be discovered by the rest of humanity, giving the impression it has suddenly appeared, and given its endemicity create a fake pandemic to motive the sale of vaccines. Variants of the origin myth can then be used to create fear, to increase vaccine take-up, and the ‘accidental’ revelation of the secret GoF formula might be used to proclaim technological prowess (and potentially also to create future scapegoats and confusion if that is required).

Intentional spread of non-infectious clones:

- If we set aside pre-existing endemicity then all that is required is some functional amendments to some existing localised virus (from a bat, say), either known or newly discovered. Because it is from a bat GoF design of a human version would be impossible, hence, deadliness and transmissibility could not be ‘designed in’. It won’t ‘go viral’ because it isn’t infectious and could not cause a pandemic. However, you could clone it so that it contains novel and deadly looking features, but you don’t much care what its functional features are apart from that because the symptoms will be non-differentiable from other respiratory viruses. You would then simply need to distribute these clones artificially to make it look like a virus that spreads. Also, despite not being any more deadly than other coronaviruses it might still poison people and cause some morbidity. You would then invent a vaccine and create a test designed to detect the DNA associated with the ‘virus’. This, in summary form, is the hypothesis of JJ Couey [here]16. We understand this hypothesis is partly inspired by the video lecture given by Dr James Giordano.

Relevant to both scenarios, but as yet largely ignored as a factor in the events of the past few years, is the well-known and widely researched propensity of chronic stress to manifest as physical illness. The covid era was, after all, characterised by what was the most sustained and sophisticated and co-ordinated propaganda campaign ever imposed on human populations, specifically intended to increase fear and anxiety. In his video lecture, Giordano specifically invokes this aspect of how a pandemic could be manufactured17.

Note that the ‘non-infectious clone’ theory would not create a self-sustaining global pandemic but might instead be considered to be akin to localised chemical attacks, where people would inhale an airborne pathogen but not transmit it.

Acknowledging the operational difficulty involved in continually manufacturing and distributing viral clones, in respect of JJ Couey’s thesis, clones may only have been needed to have been deployed in hot spots (NYC and Bergamo Italy etc.) in 2020 to trigger a fake pandemic, and that subsequent positive SARS-CoV-2 cases, from then on, were a combination of PCR tests cross reacting with other viruses to cause false positives and/or natural endemic SARS-CoV-2 virus circulating at a low background rates.

There is a third explanation, elements of which actually overlap with the foregoing: that the characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 as a novel entity is entirely an artefact of virological testing and genomic sequencing methods. This is a hypothesis we will not be expanding upon here but are equally happy that others examine this possibility in further detail.

Conclusion

The virus which has become known as SARS-CoV-2 doesn’t appear to be that novel when looked at from several angles. Claims that something novel emerged in 2019 – whether or not through Gain-of-Function experimentation appear to be without foundation.

Firstly, it appears to be just another coronavirus, of which at least eight other similar such viruses have been detected since the 1980s. Furthermore, the lethality of the latest addition to the collection looks as if it is following a similar course to the others – overestimated soon after discovery only to be downgraded later. Attribution of virus lethality suffers from the fallacy of the single cause – the presence of the virus is presumed to be enough to explain death and illness independently of comorbidity and the medical treatments applied (or not). Likewise, the clinical characteristics of illness associated with SARS-CoV-2 also appears to be largely indistinguishable from other coronaviruses and other viruses which, in any event, are often multiply present as coinfections.

Secondly, the much-touted ‘special’ structural characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 do not – on deeper scrutiny – appear that unusual. Similar features having been identified in other apparently unremarkable viruses. Even the gp120 HIV inserts might have originated from wherever that sequence can be found elsewhere in nature and in man.

Thirdly, the complexity of the relationship between genotype and phenotype is too great and poorly understood to make the deliberate act of engineering the pathogenicity of viruses ever reliably achievable. Due to ‘the curse of dimensionality’, only the timescale of natural evolution could deliver the time and space needed for this. A review of so-called Gain-of-Function and Loss-of-Function experiments does not suggest that much practical and / or relevant progress has been made in overcoming this insurmountable barrier.

Fourthly, the possibility of long-standing – but hitherto unnoticed – endemicity of SARS-CoV-2 in various animal reservoirs at various times cannot be ruled out. Inherent limits to the dependability of phylogenetic analysis and antibody testing mean that we have, in Popperian terms, an unfalsifiable hypothesis that the virus, or its variants, were endemic and have been for some unknown time.

Fifthly, it appears that the engineering of clones carrying genetic material is and has been standard practice around the world for some time. Given the above, the creation and distribution of such clones might appear to be a much more likely explanation for the rapid spread of a particular sequence around the world than the natural spread of a novel pathogen from a class of viruses known to be highly mutable.

Given the above, we would suggest that Gain- of-Function should be more aptly known as Claim-of-Function.

We are therefore left entertaining four competing hypotheses that might explain the viral ‘signal’: (i) pre-existing zoonotic endemicity; (ii) a natural zoonotic act that spontaneously created the virus at the right place in the right time in Wuhan; (iii) a Gain-of-Function lab leak; or (iv) the (intentional?) distribution of non-infectious clones producing a global viral signal. Given the results of our analysis we believe that the available virological and epidemiological evidence does not adequately support either the lab leak or the wet market theories for the origins of the virus.

Finally, none of the above is meant to excuse shortcomings in the discipline of virology (which seems to have lost its way over the past decades), nor express approval for Gain-of-Function research. Much research in the area looks to be neither ethical nor useful, and whilst we disagree that scientists can make viruses with pandemic potential, it is possible, or in fact even likely, that such experimentation may pose dangers locally (but not globally). Moreover, as we have seen, the constant hunting for viral sequences and frenzied analysis of those thought to be novel help lay the foundations for a constantly fearful humanity, empowering those who wish to impose ‘pandemic preparedness’ on the world, with its paraphernalia of control mechanisms and attendant loss of freedoms.

In this article, we are not intending to defend those who may have conducted such research, but nor do we think it is right to solely blame such research when the evidence for a spreading pathogen having caused a pandemic of a novel disease is so weak. It is perfectly possible to simultaneously believe (as we state above) that such research is unethical and that it did not (directly at least) cause the ‘covid pandemic’, which was an iatrogenic phenomenon. In this regard if there actually was a function gained by the virus it was the power to help trick humanity into a dramatic act of self-harm.

Postscript

Is there any evidence for endemicity pre-pandemic? The presence of SARS-CoV-2 was reported in Barcelona wastewater samples in a pre-print published in by Chavarria-Miró et al in June 2020. The wastewater samples were archived from December 2019 to May 2020, with positive samples reported from as early as March 2019, a full 12 months before Covid-19 was declared a pandemic. However, when their pre-print was finally published, here, there was no mention of the positive sample from March 2019 and the earliest sample reported was from January 2020. This article reports failed attempts to discover the reasons for this volte face and also summarises numerous studies, mainly from Italy, where pre-pandemic SARS-CoV-2 positive samples were reported.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to friends and colleagues for encouragement, feedback, insight, review and correction.

Many suspect that cases of renal failure associated with ‘covid’ are actually adverse effects caused by remdesivir administered as a putative treatment.

MERS-CoV and MERS-CoV-like antibodies have been identified in dromedary camels. Camels are indigenous to the middle east. Uniqueness seems to have stood out as the explanatory variable and it isn’t clear whether any other animals were tested. Perhaps if the virus had been detected in Scotland, wild haggis would have been the prime suspect?

The Duesberg hypothesis – that HIV does not cause AIDS has some striking parallels to the story of SARS-CoV-2. It is rooted in the idea that HIV is a passenger virus that does not cause the pathology called AIDS, which is instead caused by drug use (in Europe) and malnutrition (in Africa).

Sceptics might believe the public never get to see any information they don’t want us to see.

Bat-origin RaTG13 is currently the most phylogenetically related virus to SARS-CoV-2.

While we don’t concur with any presumption that the variants were themselves more or less pathogenic or transmissible this is a useful heuristic of the likely evolution of any coronavirus in a large host population (or the best available to date).

We use the word requirement here rather than biological fitness because it better matches the fact that it must functionally meet some human goal.

Ralph Baric: “When you adapt a coronavirus to another species …just putting a human receptor in and using a mouse model is not predictable of human transmissibility”.

Likewise, presuming the source virus is from another animal we have the challenge of crossing the species barrier to contend with.

Infected ferrets were reported as having lesions showing moderate meningitis and encephalitis with lymphocytes in the thalamus, compared to animals who were infected with the wild virus. However, no tests were done for bacterial meningitis hence this evidence, coupled with the small sample size is very weak.

Clearly this research aims for GoF, and if one acknowledges that such an activity is inherently criminal then these experiments themselves are, at the very least, unethical. Also, who is to say that Loss-of-Function is any less dangerous than Gain-of-Function?

It should be recognized that the mouse models used in these studies and extensively investigated in the literature are based on an artificial expression of the h-ACE2 receptor that does not fully reflect the expression pattern of the same receptor in humans and consequently the immune response associated to infection.

As it stands the evidence for this does not withstand even cursory scrutiny.