The Incompleteness Theorem

… and the resurrection.

By Chris Waldburger

I have long been fascinated by one of the towering giants of mathematics and logic, Kurt Gödel.

His famous incompleteness theorem proved that any mathematical system always relies on truths outside that system. Mathematics can never stand alone.

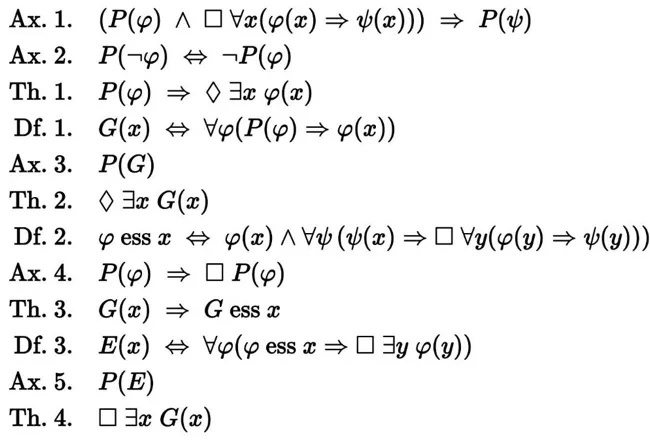

He then used that same system to demonstrate the existence of God by means of his own mathematical version of ‘the ontological argument’, seen below:

(Read here for a line by line explanation.)

After publishing his famous theorem in Vienna in 1931, Gödel left Austria in 1939, for Princeton in the US, in order to avoid military conscription during World War II. He would become an American citizen and live there for the remainder of his life.

Over and above his incompleteness theorem and his ontological argument, he is also remembered for his discovery of a ‘loophole’ in the American Constitution, now known as ‘Gödel’s loophole’. He never shared the details. He tried to bring it up at his citizenship hearing but the judge moved on to avoid an awkward conversation.

It is believed Gödel would likely have pointed out that Article V of the US Constitution, which allows for the orderly and limited amending of the Constitution, is liable to amendment itself, thus allowing for the possibility of the Constitution being dismantled by constitutional means.

(I have already written and spoken about the fact that covid was the great revelation that liberal constitutions are always ultimately mere pieces of paper, reliant upon interpretation and elite control thereof. ‘Sovereign is he who decides the exception.’ See here and here. I will write more on this issue of where political sovereignty truly lies in the coming weeks.)

There is a connection between all three of these concepts. Gödel’s great theme is that truth is never self-contained within a system. It must come from Somewhere Outside in order to appear Within…

I am writing about this great man now having been reminded him of twice in recent months.

The first was his ‘appearance’ in the film Oppenheimer. Gödel ended his career at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, alongside Oppenheimer and Einstein.

Einstein reportedly said that as his “own work no longer meant much, that he had come to the Institute merely to have the privilege of walking home with Gödel.”

Gödel has only one line in the film, when he mysteriously states, “Trees are the most inspiring structures.”

The second reminder of the man was an essay I came across online in Aeon magazine.

The essay, entitled ‘We’ll meet again’, is about the discovery of letters Gödel wrote to his mother as she entered the final days of her life.

She had asked him whether one could rationally hope in the existence of an afterlife, and he, the greatest logician of our time and perhaps even of all time, had affirmed that yes, we can, and that, yes, we shall meet again.

In the essay, the writer, Alexander Englert, a current fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study, quotes from a letter Gödel wrote on 23 July 1961 to his mother on the question of the existence of an afterlife:

If the world is rationally organised and has meaning, then it must be the case. For what sort of a meaning would it have to bring about a being (the human being) with such a wide field of possibilities for personal development and relationships to others, only then to let him achieve not even 1/1,000th of it?

Does one have a reason to assume that the world is rationally organised? I think so. For it is absolutely not chaotic and arbitrary, rather – as natural science demonstrates – there reigns in everything the greatest regularity and order. Order is, indeed, a form of rationality.

Englert explains further:

He deepens the rhetorical question… with the metaphor of someone who lays the foundation for a house only to walk away from the project and let it waste away. Gödel thinks such waste is impossible since the world, he insists, gives us good reason to consider it to be shot through with order and meaning.

In other words, the world is a place of ‘soul-making’. This is the essence of the world. It is a place of truth and order, despite the tumult of history; truth and order that the soul can apprehend. But because this world does not complete the job, the soul must find completion in another form of life.

Englert later explicitly makes the link between this idea and the incompleteness theorem:

Although unmentioned, his belief in an afterlife is also imbricated with the results from his incompleteness theorems and related thoughts on the foundation of mathematics. Gödel believed the world’s deep, rational structure and the soul’s postmortem existence depend on the falsity of materialism, the philosophical view that all truth is necessarily determined by physical facts.

The human mind, in discovering truth, truth that always transcends a closed, earthly system, is participating in something greater than the physical world. The mind is something more than the atomic, more than a closed system. And if it is a participant in something greater even in this life, it will have an opportunity to experience this greatness even further in the afterlife, because reality itself demands it.

The great father of quantum mechanics, Max Planck, believed in something similar, when he posited:

I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.

This is an old argument, at least as old as Plato, who also believed in the immortality of the soul. Because the soul can perceive universal truths, it cannot be material. If it is not material, then it is not mortal.

As Aristotle and then Aquinas would point out, however, the human soul is the form of the body. It does not and cannot stand alone. It belongs with the body, even if it has a substantial existence apart. It is the inner principle of the body that makes it a human body, with the potential of rational thought and will. Thus, if the soul is immortal, then the body must have some future hope too.

In this fashion, they were pointing to a truth already known to the prophet Isaiah, centuries before Plato and Aristotle:

But your dead will live, Lord;

their bodies will rise—

let those who dwell in the dust

wake up and shout for joy—

your dew is like the dew of the morning;

the earth will give birth to her dead.

And even before Isaiah, the Book of Job had recorded the great longing of the innocent man who suffered unjustly:

I know that my redeemer lives, and that in the end he will stand on the earth. And after my skin has been destroyed, yet in my flesh I will see God; I myself will see him with my own eyes—I, and not another. How my heart yearns within me!

Thus, the prophets and the philosophers are in agreement: to believe in the immortality of the soul, one must logically believe too in some kind of the resurrection of the body.

The central theme of the New Testament may be regarded as resurrection, and it may not be too much of a stretch to suggest that the apostle Paul may have been the foreunner of the incompleteness theorem, as Englert seems to imply in the conclusion to his essay on Gödel:

The belief that it is our essence to become something more than we are here explains why Gödel was drawn to a particular passage in St Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, which I discovered when perusing his personal library at the archives of the IAS. In a Latin, pocket-sized edition of the New Testament, Gödel jotted at the top of the title page in faint pencil: ‘p. 374’. Following this reference, one is led to Chapter 15 of St Paul’s letter where Gödel marked verses 33 through 49 with square brackets and drew an arrow to one verse in particular. In the bracketed verses, St Paul describes our bodily resurrection. Employing the metaphor of crops, St Paul notes that sown seeds must be destroyed in order to grow into plants that it is their nature to become. So too, he notes, will it be with us. Our lives and bodies in this lifetime are only seeds, awaiting their destruction, after which we will grow into our ultimate state of being. Gödel drew an arrow pointing at verse 44 to highlight it: ‘It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power. It is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual body.’ For Gödel, St Paul had apparently arrived at the correct conclusion, albeit by prophetic vision as opposed to rational argument.

If Gödel was inspired by Paul, it is also interesting that in making the case for some kind of resurrection, he is standing alongside Jesus in his dispute with the high Jewish authorities of the Temple:

That same day the Sadducees, who say there is no resurrection, came to him with a question. “Teacher,” they said, “Moses told us that if a man dies without having children, his brother must marry the widow and raise up offspring for him. Now there were seven brothers among us. The first one married and died, and since he had no children, he left his wife to his brother. The same thing happened to the second and third brother, right on down to the seventh. Finally, the woman died. Now then, at the resurrection, whose wife will she be of the seven, since all of them were married to her?”

Jesus replied, “You are in error because you do not know the Scriptures or the power of God. At the resurrection people will neither marry nor be given in marriage; they will be like the angels in heaven. But about the resurrection of the dead—have you not read what God said to you, ‘I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’? He is not the God of the dead but of the living.”

When the crowds heard this, they were astonished at his teaching.

We are bombarded by the powers that be with this strange notion of ‘The Science’, of ‘settled science’.

We are told that the age of ‘politics’ is over and that only extremists deny the new scared tenets of the media and the mass, planetary bureaucracy.

If I am criticized for questioning covid and climate science, I am simply mocked if I go deeper and question the foundational story of evolution, the attempt to explain the world in purely material terms.

Yet the witness of the greatest minds of our times, men like Gödel, belies this fake, ideological poison, the state religion of a dying age.

I agree with Gödel.

The dead will live.

Chris Waldburger is a writer based in Africa, from where he criticises our current global regime. His work can be found at ChrisWaldburger.substack.com <http://ChrisWaldburger.substack.com>. His debut book, /Rage and Love: A Memoir of White South Africa in an Age of Destruction <https://a.co/d/85mUgIR>/ is available on Amazon.